.

This article is re-published from The Conversation Indonesia (TCID)

.

Indonesian central government devolved its authority over the education sector to local governments more than 18 years ago. Since then, the delivery of basic education services depends on the capabilities of more than 500 district administrations across Indonesia.

We conducted a telephone survey in 2018 to document and analyse education policies issued at the district level. Our survey found the majority of policies to improve students’ grades are ineffective.

As Indonesia’s general and presidential elections are approaching, we call for the new administration to evaluate these education policies. We also encourage the central government to work with local governments as equal partners in improving the quality of education.

Ineffective policies

Analysing 34 education policies from 13 districts across the country, we found district administrations focused more on improving student learning outcomes as indicated by students’ test scores, as opposed to improving access to schooling. This is reasonable given that participation in basic education is already high.

These administrations seem to consider teacher skills and income as major constraints to achieving their objectives. That’s why one-third of the 34 policies are related to teacher development programmes. This includes training to improve teaching skills.

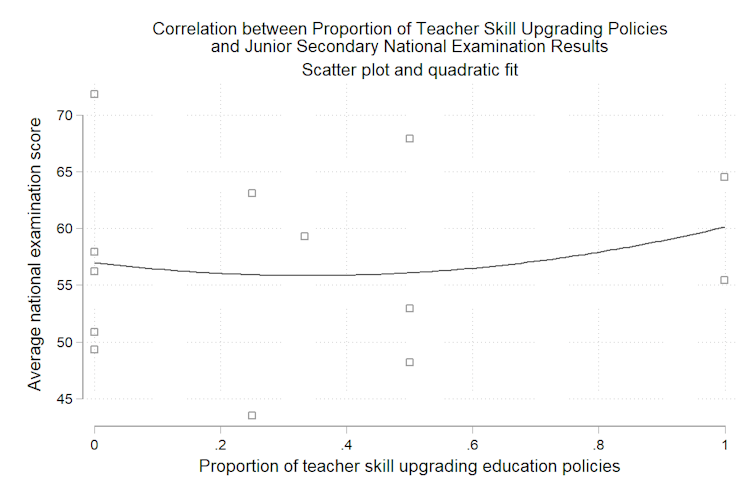

However, we find no evidence that these teacher-focused policies improve learning outcomes. The proportion of policies on training is not correlated with the junior secondary national examination scores, as shown in the graphic below.

SMERU 2018 Phone Survey

Other interesting findings

After interviewing 22 respondents in 13 districts, we also found most districts operate multiple education policies of different types. Most of our respondents are heads of education agencies across Indonesia. From them, we know that each district has around three policies on average. Four districts have only one policy, and one district has six policies.

Of these policies, one-third cover non-teacher issues, including allowances for poor children, school infrastructure and facilities.

The third-most-popular policy is giving bonuses to all teachers. The main reason is that teacher salaries, especially for contract teachers, remain low.

These policies are all homegrown, meaning they originate from within the districts, not from other districts or from the central government.

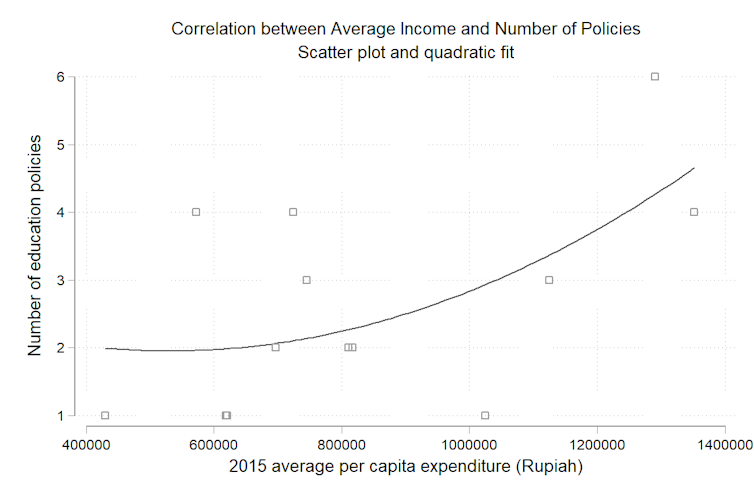

We also find that the richer a district is, the more education policies are being issued. Our statistics (below) show that a doubling in district average household income correlates with more education policies. The districts with only one policy in our survey are indeed the poorest.

SMERU 2018 Phone Survey

About the survey

The survey is part of the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Programme to evaluate education policies implemented by the central and local governments in Indonesia.

At first, we chose the best-performing 26 districts based on their national examination scores for junior secondary students.

While districts are responsible for services at primary and junior secondary schools, we focus on the latter because the examination at this level is nationally standardised.

The average junior secondary national examination score in these districts between 2010 and 2015 was 70.2, much higher than the national average of 67.8 during the same period. These top districts are spread across the country: eight in Sumatra, 10 in Java, one in East Nusa Tenggara, four in Kalimantan and three in Sulawesi.

This survey focuses solely on the most successful districts, as we hope to glean insights and findings that less successful districts can learn from.

After many attempts to contact the 26 districts, we were only able to document education policies in 13 districts.

Although these were the country’s best-performing districts between 2010 and 2015, their education performance was relatively low in 2017. That year, their average junior secondary national examination scores stood at 57 points.

What’s next

Our mapping of education policies at the district level is only the first step. A policy choice could succeed only if the detailed policy design is appropriate and that design is faithfully executed.

So, we have only begun to scratch the surface of district education policies and how they could improve learning.

Since 2001, Indonesia has delivered education services to more than 500 districts. The effectiveness of this service depends on the history, cultures and institutional capability of each district under the coordination of the Education and Culture Ministry.

Our research supports our belief that it’s time to evaluate policies in education almost 20 years after the national government shared authority over education management with district governments.

We hope the nation’s newly elected president and vice-president will commit to improving the quality of elementary and secondary schools by reviewing these policies in the districts.