Highlights

- The socioeconomic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us that the social assistance system in Indonesia needs to be improved in order to respond to crises caused by a nonnatural disaster.

- Lack of coordination and synchronization in the data collection and management of the information of social assistance beneficiaries and in the distribution of assistance are at the root of all problems that the central government still cannot solve holistically.

- There needs to be actors who are able, and have the authority, to coordinate a social assistance system that specifically responds to economic shock triggered by nonnatural disasters such as a pandemic.

COVID-19 Pandemic and the Government’s Responses

Economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the fore the call for improving the social assistance system in Indonesia. The pandemic, which has caused economic shock and crisis, is one that is unprecedented, causing uncertainty in the society. This situation leads to an urgency for a comprehensive improvement of the government’s social assistance system. Also, this situation demands that policymakers respond quickly to the turmoil in the society. These two measures can only be achieved if there is a mechanism for coordination and synchronization that involves concerned parties in various levels of the government.

The need for improving the social assistance system is apparent from various issues related to data collection and management of social assistance information and distribution of assistance during the pandemic. The monitoring results of national and local media coverage of DKI Jakarta Province, West Java Province, Kabupaten (District of) Maros (South Sulawesi), Kabupaten Badung (Bali), and East Nusa Tenggara Province in the period of 21 April–9 June 2020 reveal two major issues. First is lack of coordination in, and unclear mechanism for, the distribution of social assistance. The second one is data inaccuracy of social assistance beneficiaries. Why have these things happened and what should be corrected?

Issues regarding Beneficiary Data and Distribution System of Social Assistance

What happened in DKI Jakarta Province, West Java Province, and Kabupaten Maros gives us a glimpse of the lack of management in beneficiary data and distribution of social assistance in Indonesia. Polemics about social assistance involves actors from regional to the central government levels.

In West Java Province and Kabupaten Maros, there were protests and rejection of the social assistance by the people because of issues related to its distribution during the pandemic. In several areas in West Java, various parties—from the people to village officials—rejected social assistance, citing that the data was inaccurate so that the assistance did not reach all the intended targets or was mistargeted. In Kabupaten Maros, the people protested because those who should receive the assistance did not.

The regional governments of both regions responded differently to the protests and rejection. West Java governor, Ridwan Kamil, shifted the focus to the central government. He stressed the importance of synchronizing the social assistance distribution so that there would be no misunderstanding as a result of the differences in time and method of distribution. In this regard, President Joko Widodo responded positively to the suggestion.

“Our suggestion is that the eight channels of assistance from the central government and regional governments are synchronized by, if possible, the Coordinating Ministry of Human and Cultural Development, so that all channels are under one regulation, one method, and one period of time. It is because many ministries do things their own way, confusing the people. Some received the assistance before the others, some received them late, some even thought they were not getting any and ended up blaming the RT/RW [neighborhood units] administrators, launching a protest and so forth and so on.” (Ridwan Kamil, West Java governor, Detiknews, 28 April 2020)

“I have asked the coordinating minister for human and cultural development to talk with the governors so that it corresponds with what Pak Emil [Ridwan Kamil] said, especially for the timing, so that the people receive the assistance.” (President Joko Widodo, Humas Jabar, 28 April 2020)

On the other hand, the Regional Government of Kabupaten Maros revealed a weakness in the social assistance beneficiary data collection. The problem is related with the national database for social safety net, namely the Integrated Social Welfare Database (DTKS). The Social Affairs Agency of Kabupaten Maros said that the data used for the social assistance distribution has not been updated and efforts to update the data are hampered due to the pandemic.

“Actually, we use the 2017 data. For this year, actually we have planned to update the data and have even trained the team assigned for that, but due to the pandemic, the plan was delayed... because the problem was, many of the people protesting the assistance distribution still use an old ID number or don’t have an e-KTP [electronic ID card] yet, resulting in the central [government] not validating their data.” (Prayitno, head of the Social Affairs Agency of Kabupaten Maros, TribunMaros, 14 Mei 2020)

In early May 2020, the central government, in this case, the Ministry of Social Affairs, and the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta were caught in polemics related to the distribution of social assistance that overlapped. The polemics happened between coordinating minister for human and cultural development, minister for social affairs, and DKI Jakarta governor. This was revealed by the coordinating minister, as quoted below.

“Not to mention the synchronization and coordination. For example, we and DKI Jakarta are at the moment in a tug-of-war, trying to synchronize the data. In fact, I was a bit tense with the governor [Anies Baswedan], I had to rebuke the governor.” (Muhadjir Effendy, the coordinating minister for human and cultural development, CNN Indonesia, 6 Mei 2020)

The DKI Jakarta governor responded by saying that what they had done was ”filling the gap” or giving assistance to people who had not received it from the Ministry of Social Affairs. The overlap is the consequence of the timing of the distribution. The governor’s response demonstrates that the Regional Government of DKI Jakarta pays special attention to potential risks of social unrest that could happen (or have happened—in West Java, for example).

“The central government was going to distribute the social assistance to the poor and the vulnerable, affected by COVID-19, later on 20 April 2020. That is why the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta made a move to distribute food assistance to the people in order to avoid food scarcity that can lead to social unrest. We, the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta, have distributed the assistance earlier to fill the gap.” (Anies Baswedan, DKI Jakarta governor, Kompas, 8 Mei 2020)

The polemics involving the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta and the central government were resolved through an agreement to coordinate the social assistance distribution for the next period. This was expressed by the coordinating minister for human and cultural development: “To avoid any overlap, DKI Jakarta deputy governor and the minister for social affairs have agreed to distribute the assistance by kecamatan- [subdistrict-] based zones (CNN Indonesia, 11 Mei 2020).

Unraveling the Tangled Web of Social Assistance Distribution: Mapping the Stakeholders

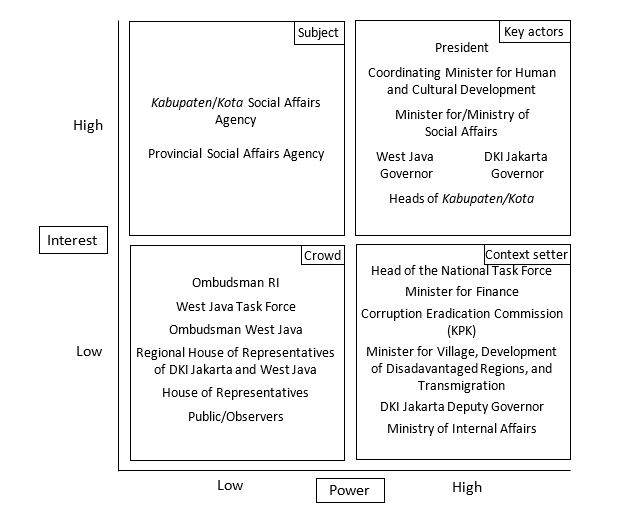

To be able to see the problems in social assistance distribution more clearly, we conducted an analysis of stakeholders from national and local online and printed media in DKI Jakarta Province, West Java Province, and Kabupaten Maros from April to June 2020. At the initial stage, the actors identified to be involved in the problems of social assistance distribution in the three regions were mapped out based on their levels of power and interest.

The level of power can be seen especially from their authority based on the regulation related to beneficiary data collection and social assistance distribution. The capacity to influence other actors, which can be identified from the news, is also used as a reference to see the level of power.

Meanwhile, the level of interest of an actor is shown mainly from the indicator of emphasis on an issue, analyzed from the actor’s statements (content analysis method) in news articles about social assistance. Furthermore, the frequency of an actor’s appearance on mass media, either as the person whose statement being quoted or as an object mentioned by other parties, is taken into consideration to determine the actor’s level of interest.

Based on the levels of power and interest, the stakeholders are divided into four categories: (i) key actors, which are actors with high levels of power and interest; (ii) context setters, which are actors with a high level of power or influence but a low level of interest; (iii) subjects, which are actors with a high level of interest but low levels of power or influence; and (iv) crowd, which are actors with low levels of power and interest (Bryson, 2007; Reed et al., 2009).

Results of the mapping show that there are at least six key actors related to social assistance issues in DKI Jakarta Province, West Java Province, and Kabupaten Maros, namely President Joko Widodo, coordinating minister for human and cultural development, minister for social affairs, DKI Jakarta governor, West Java governor, and heads of kabupaten or kota (city) in the three regions (Figure 1). These key actors give emphasis on different issues so that they are not connected to several clusters of issues. In this regard, governors and heads of kabupaten/kota are the main actors at the local level that have important roles in their respective regions. This is seen from their influence or from the regulations related to social assistance. At the same time, President Joko Widodo, coordinating minister for human and cultural development, and minister for social affairs are the key actors at the central level whose authority and influence include the whole country.

Figure 1. Results of stakeholders mapping

The main issue is that, of the six key actors, none can be said to play the role in or have a direct influence on the efforts to holistically solve the problems of beneficiary data and social assistance distribution mechanism. The actors who are policymakers tend to only focus on programs directly under their authority and tend to respond to issues that are trending.

From the regulation and authority side, coordinating minister for human and cultural development at the national level has the potential to coordinate efforts to overcome problems related to social assistance, at least at the macro context. The function of the coordinating minister for human and cultural development is to coordinate the Ministry of Social Affairs and Ministry of Village, Development of Disadvantaged Regions, and Transmigration and acts as chief of the advisory board of the COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force (National Task Force).

Based on Presidential Regulation No. 68 Year 2019 on the Organization of State Ministries, the Ministry of Human and Cultural Development’s functions include, among others, coordination and synchronization of the formulation, determination, and implementation of ministerial/institutional policies related to issues respective of each field (Article 49, letter a), and coordination of the execution of duties, supervision, and administrative support to all organizational elements within the Ministry of Human and Cultural Development (Article 49, letter c). This means that the minister for human and cultural development currently has the position and authority to coordinate actors at the central and regional levels, as reflected in the following statement.

“Please bear in mind that we are constantly evaluating. So, don’t be surprised if, halfway through the process, there will be changes based on the monitoring my team has been conducting, and the results will be reported to the minister for social affairs and the minister for village affairs for further improvement.” (Muhadjir Effendy, minister for human and cultural development, Kompas, 12 Mei 2020)

The coordinating minister for human and cultural development was said to coordinate the evaluation in all regions, as seen in the quote above. However, there is no news about the follow-up of the plan or regulation on the revision of the mechanism for data collection and social assistance distribution in response to the problems that arose. The issue of social assistance was once again discussed during a closed meeting on 19 May 2020 led by President Joko Widodo. He stressed that the procedures for distributing social assistance were too long and complicated, as seen in this quote.

“The procedure is too complicated, whereas the situation is not normal and is extraordinary. Once again, this needs to be accelerated. I want the regulation to be as simple as possible without sacrificing accountability. (President Joko Widodo, Youtube, 19 Mei 2020)

The Ministry of Social Affairs responded directly by emphasizing the need for prioritizing acceleration, accuracy, and accountability in social assistance distribution.

“The message from president is to be swift, accurate, and accountable. So, fulfilling these three requirements are what we are focusing on, even though it is not easy, especially with accountability that we must always pay attention to and pursue. (Juliari Batubara, then minister for social affairs, Youtube, 19 Mei 2020)

On the other hand, cases in West Java and DKI Jakarta reflect the principal need for coordination and synchronization in social assistance distribution. In the cases of DKI Jakarta Province, the coordination between the provincial government, Ministry of Social Affairs, and Ministry of Human and Cultural Development resulted in a solution for the next batch of distribution. This shows that the solution through coordination is basically achievable; the problem is the lack of effort to solve the social assistance problems holistically. Actors in the regions have taken steps to deal with the problems, but these measures have only been partial or technical. Actors at the central level do not seem to have done something to solve the problems holistically in terms of regulations and mechanism for the assistance distribution.

On various news, Ministry of Social Affairs focused on technical issues of the distribution that was part of its responsibility. In the context of coordination of the social assistance distribution, actually Ministry of Social Affairs has the authority to execute, supervise, and provide technical guidance, as stipulated in Presidential Regulation No. 68 Year 2019 and Presidential Regulation No. 46 Year 2015 on the Ministry of Social Affairs.

Furthermore, based on the Decision of the Chief Executive of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response Acceleration Task Force No. 18 Year 2020 on the Second Amendment of the Decision of the Chief Executive of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response Acceleration Task Force No. 16 Year 2020 on the Description of Duties, Organization, Secretariat, and Working Procedures of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response Acceleration Task Force, the Ministry of Social Affairs plays the main role in the operations, recovery, and basic services, tasked with providing support and guidance to accelerate recoveries from the socioeconomic impacts in the regions. The Ministry of Social Affairs leaves data collection issues to the regional governments to handle, especially at the kabupaten/kota level.

“That’s why, like it or not, we can say that 100 percent of the time, we use data pieces that are sent by the regions. The eligibility or ineligibility of the potential beneficiaries is not our responsibility. This means that the regions know better. Who are “the regions”? Well, starting from the head of the region to the village or kelurahan [a village-level administrative area located in an urban center]. (Juliari Batubara, then minister for social affairs, Detiknews, 6 Mei 2020)

“Because the authority to update the data is with the kota and kabupaten governments. (Pepen Nazaruddin, Director-General of Social Protection and Security of the Ministry of Social Affairs, , Tempo, 26 April 2020)

The quotes from the Ministry of Social Affairs above are within the context of the pandemic, which limits the ministry’s ability to conduct data validation in the field. It also shows that most of the authority to ensure data accuracy has been delegated to the regions.

This mechanism is actually in line with the Regulation of the Minister for Social Affairs (Permensos) No. 5 Year 2019, which stipulates that kabupaten/kota government conducts data collection, verification, and validation, followed by building synergy with the provincial government or Ministry of Social Affairs after going through this tiered process. During the pandemic, however, there are also potential risks that the regions may have troubles with data updating, as seen in Kabupaten Maros. Inaccurate data of social assistance beneficiaries have a negative impact on the assistance distribution from the central government as the database used was the same as the one that needs to be updated by the regions, which is the DTKS. This shows that giving full authority to the regions without good coordination is not an ideal solution.

During the pandemic, the chief of the National Task Force, a position held by the head of the National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB), is also an actor with the potential to oversee coordination. The Decision of Chief Executive of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response Acceleration Task Force No. 18 Year 2020—which includes the description of the duties and organization of the National Task Force—also states that the chief of National Task Force has the tasks to determine, execute, coordinate, deploy resources, and report progress of COVID-19 response acceleration.

The chief of the National Task Force also leads at least 24 elements from ministries that serve as executives, including the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Ministry of Village, Development of Disadavantaged Regions, and Transmigration. The minister for social affairs and governors of all provinces also serve as the advisory board, led by the coordinating minister for human and cultural development. Therefore, the chief of the National Task Force has the authority to coordinate the task of finding solutions to social assistance problems with the actors at the central level as well as actors in the regions.

However, the chief of the National Task Force has almost never made any statement concerning the social protection program. Only a few times he has given statements and those were only to convey statements made by other parties. For instance, he once advised that the Central Java governor write down his suggestions to relay to the Ministry of Social Affairs, as quoted below.

“This is a good suggestion from Central Java. Can Pak Ganjar [Central Java governor] write a letter to the task force? The copy will be sent to the Ministry of Social Affairs, about the flexibility of social assistance [distribution] so that we can follow this up immediately. (Doni Monardo, chief executive of the National Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response Acceleration Task Forc, Pikiran Rakyat, 3 Mei 2020)

The statement shows that the mechanism for evaluation and improvement of the social assistance distribution is the responsibility of the Ministry of Social Affairs as the main actor to coordinate the management of social assistance. Therefore, it can be said that, in performing his duties, the chief of the National Task Force only plays a small role in the recovery of the socioeconomic condition of the people.

Hence, the protests and rejection in West Java Province and Kabupaten Maros were a logical consequence of the fact that no actor is tasked with the main responsibility for solving social assistance problems holistically. To understand more about this, a mapping of discourses was then carried out based on issues and actors identified on the mass media.

Mapping Priority Issues Related to Social Assistance

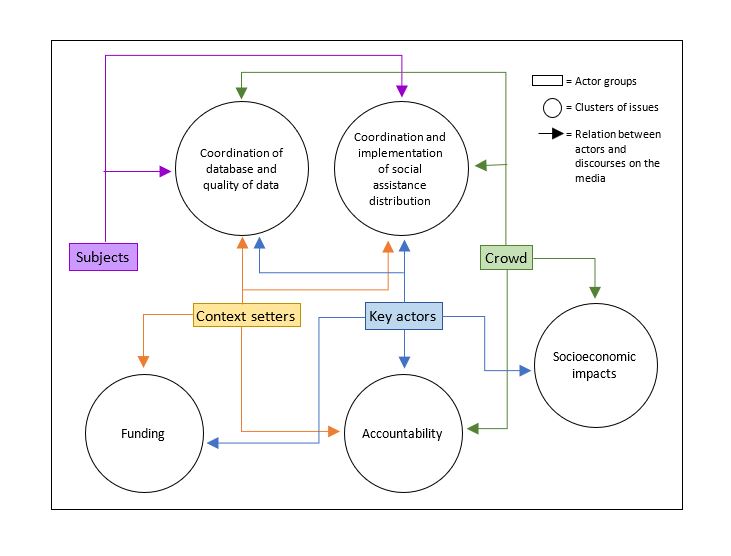

From the mapping of discourses talked about by all actors, we identified 14 issues related to social assistance. These issues were then grouped into five main groups (Figure 2). The five groups are problems which are essentially ongoing. In the context of discourses, each actor seems to give emphasis on a different issue. This indicates a difference in perspectives regarding issues that are considered important.

The key actors are directly connected to all issues discussed on the media. Meanwhile, other actors give emphasis on different issues so that it is seen that these actors have no connection with certain clusters of issues. The issues that all groups pay attention to are (i) coordination of database and the quality of data, and (ii) coordination and implementation of social assistance distribution. Both issues are the main problems in the context of social assistance distribution.

Figure 2. Results of issues mapping based on actor groups

The Need for Special Regulation in Time of Crisis

To understand the root of the problems in data collection of beneficiaries and social assistance distribution, it is important to put the prevailing rules and system in the context of the pandemic crisis/disaster that we are currently facing. In terms of disaster and social assistance, there are at least four regulations that we use as references: Law No. 24 Year 2007 on Disaster Management, Government Regulation No. 22 Year 2008 on Disaster Aid Financing and Management, and Regulations of Minister for Social Affairs No. 1 Year 2013 on Social Assistance for Disaster Victims and No. 4 Year 2015 on Direct Assistance in the Form of Cash for Disaster Victims.

Overall, three problems have been identified, namely (i) lack of special provision that regulates social protection system and distribution of social assistance/direct aid in the event of a nonnatural disaster; (ii) lack of provision that specifically regulates mechanism for data collection, verification, and validation in the event of crisis/disaster, especially nonnatural disaster; and (iii) lack of special provision related to social assistance aimed at fulfilling the daily needs of the groups affected by a crisis/disaster, such as workers suffering from layoffs or unpaid furlough due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Law No. 24 Year 2007 and Government Regulation No. 22 Year 2008, it is stated that the assistance to help beneficiaries meet their basic needs refers to several components, including temporary shelter, food assistance, clothes, safe water and sanitation, and health services. Meanwhile, in Regulation of Minister for Social Affairs No. 1 Year 2013, it is stated that the assistance includes funds for shelter, beneficiary compensation, economic strengthening, and daily allowance. The daily allowance refers to cash assistance for side dish, distributed when the emergency condition is over. In other words, there are no provisions that regulate social assistance distribution to help those affected with their daily needs in time of disaster. Therefore, it can be said that most regulations used as references for social assistance distribution during the COVID-19 pandemic are actually the ones for nonnatural disaster situations.

Data inaccuracy also occurs because the COVID-19 pandemic has created a new vulnerable group. This group, which was previously not included in the social assistance beneficiary database, is economically affected by the pandemic. This indicates that there is a need for swift and accurate data collection of social assistance beneficiaries. So far, the only regulation used as a reference for social assistance data collection has been Regulation of Minister for Social Affairs No. 5 Year 2019. This regulation, however, only stipulates the mechanism for social assistance data collection during a normal situation, not during a disaster period, so that the aspect of speed has not been taken into consideration. This is evident in the statement by the head of the Validation and Termination Subdirectorate of the Ministry of Social Affairs, as quoted below.

“That’s why in this condition, I’m worried about kabupaten or kota that don’t have budget capacity and the capability to update data. For example, when kabupaten/kota update their October, November, December data of 2019, the Ministry of Social Affairs validate them in January 2020.” (Slamet Santoso, head of the Validation and Termination Subdirectorate of the Ministry of Social Affairss, CNN Indonesia, 14 Mei 2020)

The same thing was expressed by the head of the Social Affairs Agency of Kabupaten Maros. He stressed that there is a delay in updating data due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Actually for this year, we had plan to update data and have even trained the team assigned to do that, but then, suddenly there was COVID, so, we had no choice but to delay it. (Prayitno, head of the Social Affairs Agency of Kabupaten Maros, TribunMaros, 14 Mei 2020)

Both quotes show that the current procedures for data collection require tiered process, which takes time, aside from the issue of human resources that cannot fully adapt to the pandemic-affected condition.

Therefore, it can be said that the current mechanisms and procedures cannot respond to the people’s need in a quick and accurate manner. The confusion experienced by some of the actors, such as the Coordinating Ministry of Human and Cultural Development and Ministry of Social Affairs, is understandable because, so far, there are no fixed references to use to respond to the people’s need in the event of a pandemic.

There have been measures taken for coordination purpose with the issuing of KPK Circular Letter No. 11 Year 2020 that urges that DTKS be used as a reference for data collection of social assistance beneficiaries. The circular letter, however, was issued on 21 April 2020, 50 days after the first case of COVID-19 in Indonesia was announced, or 20 days after the issuance of Government Regulation No. 21 Year 2020 on Large-scale Social Restriction (PSBB). The late or lack of synchronized timing for social assistance distribution is a logical consequence of the lack of regulation on social assistance management in time of crisis/disaster.

Anticipating Social Assistance Distribution during A Crisis

Based on the discussion above, we can conclude that there are at least two major issues to highlight, namely the unpreparedness of the bureaucracy in responding to a crisis and lack of leadership (actors with the positions and capacities to control the coordination effort). Issues such as data inaccuracy, which in turn causes mistargeting, are not new. Nevertheless, these issues become more complex when the solution still uses the fixed mechanism, which was originally designed for a normal situation, not an extraordinary one, such as a crisis. In the event of a crisis, such as a pandemic, the mechanism fails to respond to the urgency and needs of the people to receive assistance swiftly.

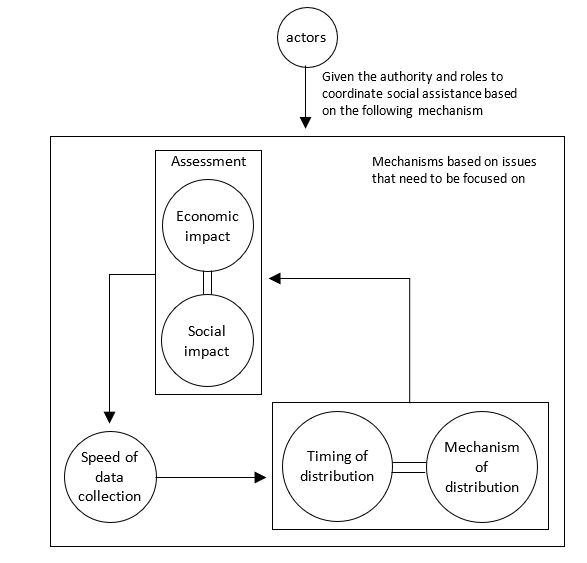

Figure 3. Social assistance distribution system during a crisis

Therefore, in order that the need for the distribution of social protection program during an economic crisis can be met swiftly, there are at least three main steps to take:

a) Designing special mechanisms and procedures for data collection of the targeted beneficiaries and distribution of social assistance swiftly and accurately, notably in the event of an economic crisis due to a nonnatural disaster. These mechanisms should be designed using, as a reference, the five main issues (Figure 2) that are currently being emphasized by the stakeholders (Figure 3).

b) Delegating the authority and roles to conduct coordination in executing the special mechanisms explained in point a).

c) Updating the database, as stipulated in Regulation of the Minister for Social Affairs No. 5 Year 2019. The updating process should be routine and be made public so that people can participate in monitoring it. The database currently available should undergo a routine updating process so that it can serve as a basis for implementing the right intervention policy in the event of a similar nonnatural disaster and/or crisis in the future.